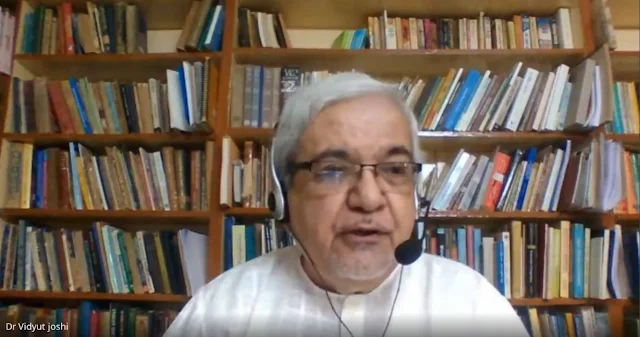

In a thought-provoking column published in Sandesh, eminent sociologist and former Vice-Chancellor Prof. Vidyut Joshi has raised urgent concerns over the erosion of intellectual autonomy and social relevance in Gujarat’s leading research and academic institutions. Building on insights from the recent paper Secret of Creating High Performing Knowledge Institutions by development economist Prof. Tushaar Shah, Joshi paints a stark picture of institutions that have strayed far from their foundational vision.

Prof. Joshi argues that many of the state’s premier research bodies—such as the Centre for Social Studies (CSS) in Surat, and the Gujarat Institute of Development Research (GIDR) and the Sardar Patel Institute of Economic and Social Research (SPIESR) in Ahmedabad—have moved from being producers of public knowledge to consultants for hire. While they were originally created as autonomous spaces for critical thinking, grounded in field-based research and societal engagement, today they are often driven by the logic of donor funding and consultancy contracts.

This transformation, Joshi asserts, has not occurred overnight. He traces a longer institutional history, pointing to how these bodies were established between the 1960s and 1980s with support from the Planning Commission and ICSSR. They were envisioned as engines of social science research that could inform public policy and deepen democratic discourse.

He credits pioneering scholars like Prof. T.D. Lakdawala, who laid the foundations of empirical economic research at SPIESR, and Prof. I.P. Desai, who grounded CSS in rigorous sociological inquiry focused on caste, community, and rural life. These figures represented an earlier generation of intellectual leadership, for whom scholarship was inseparable from social responsibility.

However, Joshi goes further back in history to show that Gujarat’s tradition of knowledge production did not begin in the post-independence era. In the 19th century, institutions like the Gujarat Vernacular Society (later Gujarat Vidya Sabha) and the Ahmedabad Education Society emerged as reformist platforms that believed knowledge should serve society. These institutions created public libraries, supported translation and publishing, and engaged with the pressing social questions of their time—be it caste reform, women’s education, or civic participation.

In contrast, Joshi laments that today’s institutions are largely inward-looking, preoccupied with funding cycles, and often isolated from both universities and the communities they were meant to serve. He observes that there is little coordination among institutions, no meaningful engagement with contemporary challenges such as informal labor, rising inequalities, or the restructuring of caste and gender in a globalized Gujarat.

Underlying this institutional crisis, Joshi suggests, is a philosophical vacuum. Where earlier scholars viewed knowledge as a means of transformation and empowerment, today’s research is often transactional, shaped by market demands rather than intellectual need. “What was once a calling has now become contract work,” he writes bluntly.

He invokes Max Weber’s idea of the “Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism” to stress that genuine institutional performance is rooted in inner discipline, ethical vision, and commitment to the public good. Joshi calls for reimagining Gujarat’s knowledge institutions in a way that restores their intellectual autonomy and reconnects them with India’s rich civilizational and reformist traditions.

Indian epistemologies, he reminds us, always viewed knowledge (gnan) as a path to liberation—not simply a tool of employment or market utility. To revive that spirit, Joshi insists, we must go beyond technical fixes and ask fundamental questions about the role of knowledge in a democracy.

He ends with a powerful reflection: “Do our knowledge institutions still have a soul? If they cannot respond to society’s deepest questions, then what purpose do they serve?” His column, while critical, is ultimately a call to reclaim the ethical and philosophical foundations that once made Gujarat’s academic institutions respected not only nationally but also globally.

Comments