By Ismail Haque*

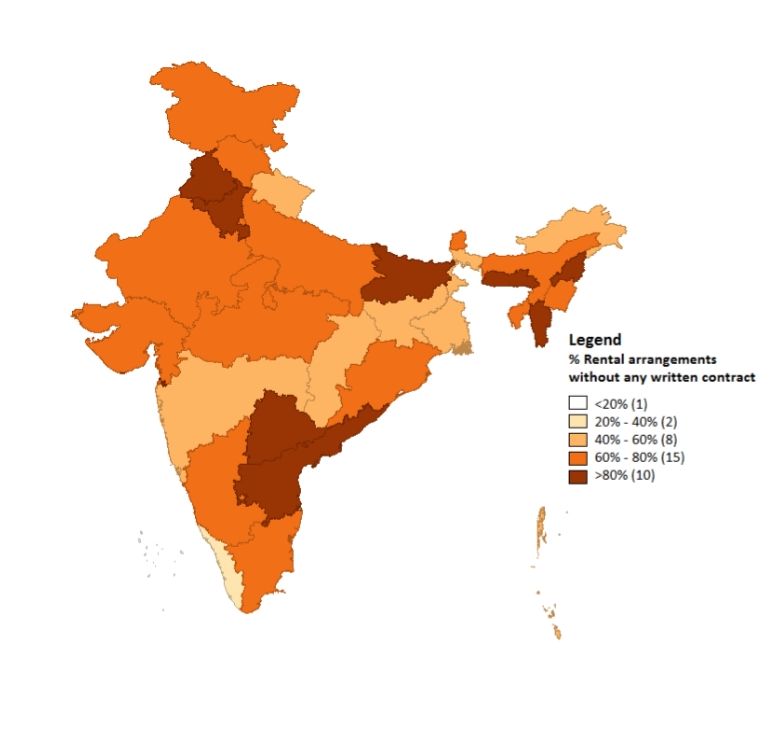

Amidst escalating urbanisation, providing adequate and affordable housing has become India’s pressing urban development challenge. Lack of secure and affordable rental housing severely affects low-income households who are bereft of homeownership in the city they work. Rental housing in metropolitan India is primarily provided by private landlords who operate outside the regulatory and judicial framework (Harish, 2021). About 70 per cent of all rental arrangements in India are not backed by a written contract of any form or are informal (NSSO 2019). A further look at its geographic variation reveals an interesting picture of rental market informality (Figure 1). For instance, more than 80% of the total rental houses are informal in the large states of – Andhra Pradesh (93.99%), Telengana (93.53%), Bihar (92.28%), Haryana (84.85%), and Punjab (83.46%).

Figure 1: State-wise distribution of Informal rental arrangements, India (2019)

Nearly 70-80% of the rental arrangements are not backed by written rental agreement in Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, which is being followed by Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh and NCT of Delhi (Figure 1). Further, among the 20 per cent supported by a written contract, only about one-fourth is registered as leases.For many low-income migrant households, informal rental housing is an affordable option and provides a foothold in the city, allowing them to access its employment and economic opportunities. In most cases, such housing is of poor quality and plagued by low tenure security, predatory landlordism, overt forms of exploitation and vulnerability for the tenant. The deficiency of tenure security and housing distress faced by impoverished tenants has also been glaringly amplified by the recent exodus of migrants from the major cities due to the Covid-19 induced lockdowns last year. In response to their distress, the Government of India introduced the Affordable Rental Housing Complex (ARHC) scheme in July 2020, with the motive of augmenting the supply of affordable rental housing for low-income and single-headed migrant households by institutional landlords in India’s cities.

Off late, the union government has also passed the Model Tenancy Act, 2021 (MTA) to revive the rental real estate business, address impediments in the current rental ecosystem, and achieve the target of ‘Housing for All’ by 2022. Up till the passing of this Act, tenants’ rights had been safeguarded by archaic and stringent Rent Control Acts (RCA) that created several negative externalities in the local housing market dynamics (e.g., minimal rent increase, the growing burden of property maintenance and ensuing quality deterioration, lengthy and complex eviction process, a disincentive to the landlord to let out property or reinvest in rental businesses, among others). With India’s rapid urban surge, growing market potential, increased inflow of FDI, massive migration, and rise in job-seeking floating population, growth in both demand and supply of rental housing will be colossal. A well-managed rental housing market can be a ‘lifeline’ for millions of home-seeking tenants. Given this context, MTA aims to establish a regulatory framework that facilitates gradual formalisation of the current renting ecosystem and create a conducive environment for the supply of affordable rental housing in urban India.

The strengths of MTA

Without a doubt, MTA is a much-needed stepping stone towards reviving urban India’s rental housing potential. With its prime motive to revitalise the rental sector, MTA provides a plethora of progressive provisions:Transparency in rental arrangements

A mandatory written and online registered rent agreement between landlord and tenant is proposed under this Act. While MTA gives enough leeway to parties involved in the rent agreement to decide rental tenure, monthly rent price and rent revision, it imposes a cap on the security deposit that can be levied from a prospective tenant at a maximum of two months’ rent for residential premises and a maximum of six months for non-residential premises. The rent price can’t be revised between the rental tenure and the landlord has to inform the tenant three months before the revision. The landlord is entitled to charge double house rent for initial two months and four times after that if the tenant fails to vacate the property even after the termination of rental tenure. Subletting of property is allowed only by entering into a supplementary agreement with the landlord’s existing rental agreement.Litigations and disputes minimisation

To minimize the incidence of litigations and disputes, repair and maintenance obligations have been assigned to both landlords and tenants. The landlord is responsible for fixing structural damages to the tenancy and undertaking whitewashing painting of walls, doors and windows. The tenant is responsible for periodic repairs, including kitchen fixtures, glass panels, maintenance of open spaces; must inform the landlord of any damage to the property urgently. The landlord cannot evict tenants during the contract period and stop providing essential services such as gas, electricity and water supply.Time-bound conflict management

To ensure speedy conflict resolution, the appointment of a rent authority with the prior approval of the state or the union territory is proposed. MTA also envisages the setting up of rent courts and rent tribunals by states to resolve disputes within 60 days of receiving the complaint.Challenges and way forward

While this new tenancy legislation has several well-intentioned provisions that can be a catalyst to transform the rental housing sector, it seeks to address the formal rental space, thereby entirely overlooking the vast grey area in the rental market, which is developed, managed and operated by informal rental providers. MTA falls short in many aspects that could potentially impact informal renting ecosystems. For instance,Exclusionary and poor blind by design

The current standards of MTA are exclusionary and poor blind by design. As mentioned earlier, the proposed tenancy agreement and online registration systems are unlikely to appeal to the informal rental market, particularly among low-income and impoverished tenants. There is no forfeit for failing to register a rent agreement, and all following provisions are only applicable to registered agreements. Consequently, the informal rental space will be bypassed entirely, contributing to solid persistence of informality with its related risks.

Inclusive and equitable access to the rental market remains a distant dream

The MTA provisions are unlikely to address the challenges of inclusive and equitable access to the rental housing market for tenants. For instance, MTA proposed a mandatory “digital platform in the local vernacular language” to facilitate hassle-free tenancy registration systems. However, addressing gaps in digital literacy and information access among informal sector tenants is a matter of concern. Aside from this, unnecessary documentation such as mandatory Aadhaar (despite no subsidy being offered) and PAN (regardless of monthly rent prices), the form for registering rental agreements increase the burden of paperwork and procedural complexity manifold. The requirement of vernacular language also seems to increase the vulnerability of poor migrant tenants since they often lack access to local social capital and housing market information.

Silent on rental market discrimination

The informal rental sector significantly transforms the social dynamics of renting ecosystems. Any person who has undertaken a housing search in India’s urban rental market would attest that only a few landlords, real estate agents, and brokers would provide or show homes to tenants that are not aligned with their caste, religion, and cultural persuasions. Such prejudices of landlords/agents against particular sections of society act as significant constraints in their access to vacancy information and rental housing having the preferred characteristics. Caste, religion, marital status, ideational differences and associated food choices are the prime levers of rental market discrimination- often leading to a pretty troubling housing search process that is time-consuming and costly (Thorat et al., 2015; Dutta & Pathania, 2016). It also triggers involuntary housing segregation on caste and religious lines, thereby creating hindrances in social cohesion and peace and perpetuating social inequality. Unfortunately, MTA is silent on rental market discrimination and fails to safeguard tenants’ right to housing adequately.

In addition, the vast majority of houses are acquired through intermediaries/brokers or informal referral services in the casual rental market. The property agents and brokers, presumably from sheer greed for commission fees, are often reported to take advantage of prospective tenants by providing partial/false information about the housing vacancy to be rented, making those tenants who have less access to social networks or housing market information and have little knowledge about tenant-landlord rights more vulnerable in this regard. This eventually creates negative externalities in the tenants’ housing search intensity and outcomes. MTA does not provide any defined guideline to curtail such malpractices in informal rental spaces.

Force majeure clause

MTA considers only war, flood, drought, fire, cyclone, earthquake or any calamity caused by nature as force majeure situations which allow the tenant to continue in possession for one month from the date of cessation of the force majeure event on the same terms as set out in the rental agreement. However, riots, civil unrest, or even a Covid-19 pandemic have not been included in the force majeure clause, resulting in a lot of ambiguity and cause for dispute in the informal renting ecosystem.Housing is a state subject. Therefore, efficient and effective implementation of MTA and its success rate is mainly contingent on the very nature of the state-centre political relationship. For instance, while Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh and Assam have already adopted the MTA; for states/UTs where archaic Rent Control Act has to be repealed or amended, timely implementation of MTA remains a challenge. Aside this, there may be some states (e.g., West Bengal) which may not implement this Act at all.

Nonetheless, as the informal rental sector is transforming from a small-scale private matter into a vibrant urban force, it deserves urgent policy interventions in the interest of more just and sustainable outcomes. In this regard, MTA must address the above-mentioned issues of the informal rental market to effectively convert its negative externalities into positive dynamics, and following measures can be helpful:

- MTA must expand its scope and coverage to address all types of rental housing sub-markets, including informal rentals. Because, policy indifference towards this ‘sunrise sectors’ may have serious implications for sustainable urban development. It means the potential negative externalities (e.g., unfair landlord-tenant relations, arbitrary rent settings, poor housing outcomes and lack of adequate basic services including health and safety risk, among others) may not get averted. It will also miss an opportunity to improve the quantity and quality of affordable rental housing.

- Incorporation of anti-discrimination clause in amended MTA will be critical to solve rental market discrimination issue because a socially inclusive housing market is the key to ensure that everyone has appropriate access to rental homes.

- In order to create an effective rental marketplace for augmenting adequate supply of affordable and quality rental housing, as envisaged in MTA, a well-managed rental housing market backed by supportive ecosystems is need of the hour. This will not only be instrumental for catalyzing the urban India’s rental housing potential but also help achieving the ‘Housing for All’.

Datta, S., & Pathania, V. (2016). For whom does the phone (not) ring? Discrimination in the rental housing market in Delhi, India, WIDER Working Paper 2016/55. Available at: https://www.wider.unu.edu/sites/default/files/wp2016-55.pdf

Harish, S. (2021). Affordable Rental Housing Complexes Scheme and Private Rental Housing in Indian Cities. Economic & Political Weekly, 56(16), 15-19.

National Sample Survey Organization (2019). Drinking Water, Sanitation, Hygiene and Housing Condition, 76th Round. Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India, New Delhi. Retrieved December 2, 2019 from http://microdata.gov.in/nada43/index.php/catalog/central/about

Thorat, S., & et al. (2015). Urban Rental Housing Market: Caste and Religion Matters in Access. Economic and Political Weekly, 50 (26 & 27): 47–53

—

*Associate Fellow at Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (ICRIER)

टिप्पणियाँ